- Home

- Karin Alvtegen

Betrayal Page 6

Betrayal Read online

Page 6

He squeezed Anna’s hand harder.

She opened the plastic folder. Read a few words and looked at him again.

‘I want to talk about the accident itself.’

The sudden feeling of encroaching danger.

‘I know that you stated that you have no recollection of the accident, but I want us to try to piece together your memories. I have the police report here.’

The woman in the chair regarded their intertwined fingers.

‘I understand that this seems like a lot of trouble. Perhaps you would rather we talked about it somewhere else? We can go to my office if you like.’

‘No.’

She sat in silence for a bit. Her eyes penetrating.

‘I don’t remember.’

‘I see that’s what it says on this paper, but the truth is that you’ve chosen not to remember. The brain functions to protect us from traumatic experiences, it chooses to repress things that are too painful to remember. That doesn’t mean that you don’t remember: everything is still inside. Sooner or later it will come to the surface and you will have to deal with it, no matter how painful it might be. And that’s precisely what I want to help you do. Help you remember so that you can move on. It’s a difficult and painful job you have ahead of you, but it is absolutely crucial. You will most likely feel angry during our conversation, but that’s all right, as long as you let your anger out. I want you to direct it to me for the time being.’

Not in here! Never before had it ventured out when Anna was present and protecting him.

‘Do you understand what I mean, Jonas? I’m here to help you, even if it doesn’t feel that way. Anna is dying and you must accept that. And you must accept that it’s not your fault, that you did the best you could. No one can ask any more of a person.’

Kalmar to Karesuando 1664, Karlskrona to Karlstad 460.

‘All I know is what I read in the police report, and of course the hospital protocol when she was admitted. That she was struck by anischemic brain damage due to lack of oxygen. What’s the last thing you remember?’

Landskrona to Ljungby 142. Help me, Anna. Stop it!

‘You had gone down to Årstaviken to eat lunch. Can you remember what day that was?’

‘No.’

‘Try to remember what it looked like. The trees, did you meet anyone, did it smell a certain way?’

‘I don’t remember. How many times do I have to tell you that?’

‘You went out on the pier at the Årstadal Boat Club.’

He had to put an end to this conversation. Had to get this woman out of the room.

Her voice droned on without mercy.

‘Anna decided to go for a swim even though it was late September. Can you recall if you tried to stop her?’

She was blocking Anna’s defence.

‘You stood and waited on the pier. Can you recall how far out she swam before you realised she was in danger?’

Anna’s head under water. Trelleborg to Mora. Damn. Not three. Eskilstuna to Rättvik 222.

The three neon pens on her large bosom were like a screeching reproach. The relentless voice that filled up every space inside him but mercilessly kept grinding away without noticing that he was about to explode.

‘When she disappeared you swam out to try and help her. Another man came by and saw what was happening. He swam out to try and help the two of you, do you remember his name?’

‘I don’t remember!’

‘His name was Bertil. Bertil Andersson. The man who helped you. The two of you managed to get her to the beach and Bertil Andersson ran to the boat club to ring for an ambulance. Try, Jonas, try to remember how it felt.’

He straightened up. He couldn’t take any more.

‘Don’t you hear what I’m fucking saying, woman? I don’t remember!’

She didn’t take her eyes off him. Just sat calmly in her chair, watching him.

He found her in the attic. She had the flowered robe on and it was the evening before he was going to move away. His bags were already packed and waiting in the hallway. The ceiling was low and she hadn’t needed a chair, only the low plastic stool that he had used as a child to reach the washbasin.

‘How does it feel now?’

Her words drove him over the edge.

‘Get out of here! Get out and leave us in peace!’

She remained sitting there. Didn’t move from the spot, but kept on boring through him with her evil eyes. Calm and collected, firmly resolved to crush him.

‘Why do you think you get so angry?’

Something burst inside him. He turned his head and looked at Anna.

She betrayed him. She lay there so innocent in her unconsciousness, but she had apparently not forgotten how to betray him. Once again she intended to leave him, alone. After all he had done for her.

Damn it.

He couldn’t trust her even now. Even now she wouldn’t do as he wished.

But he would show her. He wouldn’t let her go.

Not this time either.

She decided to go to the day-care centre. A purely physical need to attempt to evade the threat she felt. Her world was starting to come crashing down. She felt petrified, robbed of every avenue of escape. Somewhere an unknown enemy was forging secret plans, and the one person she thought she could trust had proven to be allied with someone on the other side of the battle line. Had proven to be a traitor.

The signal from her mobile forced her to pull herself together. She saw from the display that it was from the day-care centre.

‘Eva.’

‘Hi, it’s Kerstin from day-care. It’s nothing serious, but Axel fell and hit himself on the slide and would like to be picked up. I tried to get hold of Henrik, who usually collects him, but he’s not answering.’

‘I’m on my way, I’ll be there in fifteen minutes.’

‘He’s all right, he just got scared. Linda is sitting with him in the staff room.’

She hung up and set off in a hurry. The pavement on the old suburban street was broken up because they were installing remote heating and broadband, and she had to stop behind a queue of people as they let a car through.

Broadband.

Even faster.

She looked at the old turn-of-the-century houses lining the street. In this part of the neighbourhood they were big, like shrunken manor houses, not like at their end where the houses were smaller, starter opportunities for normal white-collar workers to have their own home.

A hundred years. How much had changed since then. Was there actually anything in society that was the same? Cars, aeroplanes, telephones, computers, the job market, gender roles, values, beliefs. A century of change. And it also encompassed the worst atrocities that humankind had ever devised. She had often compared her own life to how it must have been for her grandparents. So many things they had been forced to live through, learn, adapt to. Would any generation ever have to experience as much development and change as they had done? Everything changed. She could only think of one thing that was the same. Or was expected to be the same. Family and a lifelong marriage. It was supposed to function just as before, despite the fact that all external stresses and conditions were different. But marriage was no longer a common undertaking in which man and woman each took care of their own indispensable contributions. Mutual dependence was gone. Nowadays men and women were self-supporting units that were brought up to make it on their own, and the only reason they chose to get married was for love. She wondered if that was why it was so hard to make a marriage work, because the whole lifestyle depended on keeping love alive. And scarcely anyone in their child-bearing years had time to nourish it. Love was taken for granted and had to make it as best it could amongst all the things that required attention. And it seldom survived. More was needed for love to last. At least half of their friends had separated in recent years. Children who switched from one parent to the other every other week. Heart-rending divorces. She swallowed. The thought of other people’s rel

ationship problems was not making her own any easier to handle.

As daily life became more and more grey in recent years, she had thought a good deal about what was missing. And she wished that she had had someone to share her thoughts with. She had her girlfriends, of course, but lunch with the girls usually ended in general complaints about life. A statement more than a discussion about why life was the way it was. But one thing they all had in common. The weariness. The feeling of inadequacy. The lack of time. In spite of all the time-saving devices that had been invented since the houses along the street had been built, time was increasingly a rare commodity. Now they were putting in broadband to help save them even more precious seconds. Mail could be answered even more rapidly, decisions taken as soon as the alternatives arose, information retrieved in a second, information which then had to be interpreted and properly pigeonholed. But what about the human being in the background, whose brain was supposed to handle all this, what happened to her? As far as Eva knew, she had not undergone a product upgrade in the last hundred years.

She thought about the story she had heard about the group of Sioux Indians who during the 1950s were flown from their reservation in North Dakota to have a meeting with the President. With the help of jet engines they were whisked thousands of miles to the capital. When they entered the arrival hall at Washington airport, they sat down on the floor, and despite insistent appeals for them to go to the waiting limousines, they refused to get up. They sat there for a month. They were waiting for their souls, which could never have moved as fast as their bodies did with the help of the aeroplane. Not until thirty days later were they ready to meet the President.

Perhaps that was just what people should do, all the stressed-out people who were trying in vain to make their lives work. Sit down and wait to catch up. But weren’t they already sitting there all together? Not exactly waiting for their souls, but they were all sitting in their own cosy living rooms, so that they could get completely involved in all the docu-soaps on their TV sets. Act shocked at the shortcomings of others and their inability to handle relationships. How did people cope, really? And then quickly change the channel to avoid taking a look at their own behaviour. So much easier to sit in judgement over others’ behaviour from a distance.

She opened the door to Axel’s section of the day-care centre and stepped inside, pulling on the light-blue plastic slippers and continuing towards the staff room. She saw them through the glass window in the door and stopped. He was sitting on Linda’s lap eating a ginger snap. His hand was wrapped around a lock of her blonde hair and she was rocking him back and forth with her lips against his head.

The anger that had kept her going sank away and again opened up to the devastating powerlessness.

How could she ever protect him from everything that happened?

Don’t cry here.

She swallowed, opened the door and went in.

‘Look, here comes Mamma.’

Axel let go of Linda’s hair and hopped down to the floor. Linda smiled to her, shyly as always. Eva made an effort to smile back and lifted Axel into her arms, as Linda got up and came over to them.

‘He got a little bump there, but I don’t think it’s too serious. I told them not to go on the slide after it rained, it’s so slippery then but . . . They probably forgot.’

‘Feel, Mamma.’

She felt the little swelling on the back of his head. It was hardly noticeable and definitely nothing Linda should feel guilty about.

‘It’s nothing serious. It could have happened anywhere.’

Linda smiled shyly again and went towards the door.

‘We’ll see you tomorrow then, Axel. Bye.’

They held each other’s hand on the way home. When Axel had got over his anger at having to walk and not ride in the car as they usually did, he seemed to enjoy the walk.

A welcome respite.

He was the only one talking. She walked in silence and replied in monosyllables when necessary.

‘And then when Ellinor took the ball we got mad and then Simon hit her on the leg with the stick but Linda said that you couldn’t do that and then we couldn’t play any more.’

He kicked at a pebble.

‘Linda is really nice.’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you think Linda is nice too?’

‘Yes, I do.’

‘That’s good, because Pappa does too.’

Yes. When he’s not fucking someone in the shower at home.

‘Of course he does.’

He kicked the pebble again, farther this time.

‘Yes, he does, because one time when we were having a snack with her he gave her a big hug and they didn’t know I saw.’

Everything stopped and turned white.

‘What is it, Mamma? Aren’t we going to walk any more?’

In a single instant everything turned upside down.

In a second the realisation erased every hint of trust, belief, confidence.

Linda!

It was Linda.

Everything she had believed and could count on had suddenly turned into yet another lie, another betrayal.

That woman, who had just been sitting so protectively with her lips against her son’s skin, whom she had just reassured and told it wasn’t serious, she was the one, she was the person who was trying to destroy their family. Like an amoeba she had wormed her way into their life and hidden her intentions behind her feigned concern.

Was there anything to hold on to? Anything she could trust to be as it should be?

How long had this been going on? Were there any others who knew about it? Maybe all the parents knew. Only she, poor Axel’s jilted mamma, was left in the dark about whether her husband was having a secret affair with their child’s day-care teacher.

The degradation was like a razor blade pressed against her wrist.

‘Mamma, come on.’

She looked around, no longer conscious of where she was. The sound of a car approaching and slowing down. Jakob’s mother rolled down the window.

‘Hi, are you on your way home? You can ride with me if you want.’

Did she know something? Was she one of them who knew and gave her pitying looks behind her back?

‘No.’

‘Please, Mamma, can’t we?’

‘We’re walking.’

Eva gave her a swift glance, took Axel’s hand and pulled him along with her. Jakob’s mother drove alongside.

‘By the way, the parents’ group has to have a meeting soon to plan that Stone-Age camp at the day-care. Do you have time this week?’

It was impossible to answer, there were no words. She quickened her steps. Five metres more to the path across the park. Without answering she turned and pushed Axel in front of her along the path. Behind her she heard the car idle and then drive off.

Linda. How old could she be? Twenty-seven, twenty-eight? She didn’t have any children, Eva knew that at least. And now she had managed to seduce one of her day-care children’s fathers without having the least idea of what it meant to be responsible for a life.

She looked at the little body in front of her. Colourful red PVC-coated trousers like balloons around his short legs. He started to run when he saw his house.

She stopped.

Axel took a short cut through the lilac hedge and vanished through the front door. Her son in the same house as the traitor. That cowardly shit who didn’t even have the courage to admit his betrayal.

What he had done was unforgivable. She would never ever forgive him for it.

Never.

Ever.

For the first time in two years and five months he was going to spend the evening somewhere besides Karolinska Hospital. His anger at Anna’s betrayal would not let him go, and by God he would show her. She could lie there all alone and wonder where he was. Tomorrow he would tell her that he had been at the pub having a good time. Then she’d regret it, realise that she could actually lose him. If she didn’t shape

up maybe he would do as they wanted. Let go and move on. Then she could lie there and rot and nobody would give a damn.

The psychotherapist monster had managed to convince him to agree to one more conversation. It had been the only way to get rid of her, which was absolutely necessary just then. Anna hadn’t shown any remorse at all about her betrayal, and the growing compulsion had made him furious. But later he made her understand and it subsided again.

He had walked all the way into town. Drove home and parked the car on the street, and then began his walk without going inside the flat. Followed the path along Årsta Cove and then the old Skanstull Bridge towards Söder. In Götgatsbacken he passed one pub after another, but it only took one look through the big plate-glass windows to make him carry on. So many people. Even though it was a normal Thursday, people were jammed in everywhere and his courage failed him. He still wasn’t ready to go in anywhere.

Later it was so obvious that he would keep on walking, passing by all the pubs in Söder, continuing north across the locks at Slussen and into Gamla Stan, the Old Town, as if his walk had been predetermined.

He was halfway across Järntorget, heading for Österlånggatan, when he caught sight of her.

A window with a red awning.

On a bar stool, gazing straight out through the window, she sat alone slowly twirling an almost empty beer glass. He stopped abruptly. Stood quite still and stared at her.

The resemblance was striking.

The high cheekbones, the lips. How was it possible for anyone to be so similar? He hadn’t seen her eyes for a long time. Or the hands that never touched him.

So beautiful. So beautiful and utterly alive. Just like before.

He could feel the dull, heavy beats of his heart.

Suddenly she got up and moved farther back in the pub. He couldn’t bear losing sight of her. He hurried the last few metres across the square and without hesitation opened the door and went inside. She was standing by the bar. All fear suddenly gone, only a firm resolve that he had to be near her, hear her voice, speak to her.

Missing

Missing Shame

Shame Shadow

Shadow Betrayal

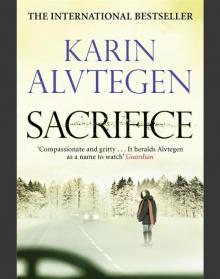

Betrayal Sacrifice

Sacrifice